Does politics in Lebanon allow for an independent government with a unified military force?

After a prolonged stalemate, Lebanon has finally elected its president. Joseph Aoun, the former commander of the Lebanese Army, has been sworn into office. In his first speech after the election, he stated that Lebanon should only have one military force: the army. This statement is logical and valid. Fundamentally, the existence of multiple military factions contradicts the essence of a modern state, which is defined by uniform sovereignty over a defined territory.

However, achieving this goal in Lebanon is far from simple. In other words, the newly elected president of Lebanon cannot realistically expect a group like Hezbollah to disarm and submit to the authority of the central government anytime soon.

By its nature, objectives, and ideology, Hezbollah sees itself less as a Lebanese entity and more as a Shiite group dedicated to advancing its religious goals on an international level. This stance stems from circumstances imposed on the people of this region in the modern era, for which, unfortunately, inadequate and short-term solutions have been adopted to address these imposed realities.

Short-Term Solutions, Long-Term Consequences

Sometimes, certain solutions may yield satisfactory results in the short term but carry inherent challenges that ultimately lead to irreversible damage. The current state of politics in Lebanon is a testament to this phenomenon.

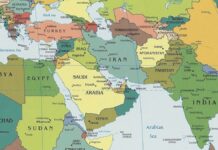

With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, its territories in Middle East were divided through colonial agreements and imposed decisions. It was evident that this method of division would not lead to the establishment of stable nations or governments in the short term. Consequently, the newly formed states witnessed various ethnic and religious divisions and conflicts.

To address the devastating human and financial toll of these conflicts, two relatively straightforward solutions were adopted for these countries: personal dictatorship and consociational democracy.

- Personal Dictatorship

The simplest path to establishing governance was the emergence of personal dictatorships, where the ruler’s will became the law, and the logic governing the system relied on loyalty and allegiance to the ruler. While this solution could bring about relative order and security in the short term, it inevitably led to the inherent problems of dictatorship, such as the absence of freedom and justice, widespread corruption, and deep divisions between loyalists and others. These issues eventually created a dysfunctional and irreparable state, culminating in revolutions and civil wars. Examples include Gaddafi’s Libya, Assad’s Syria, Ben Ali’s Tunisia, and Saddam’s Iraq.

- Consociational Democracy

The Consociational democracy approach was equally simple and convenient. Diverse ethnic and religious groups that could not form a unified nation (nation-building being one of humanity’s most challenging endeavors) reached agreements to divide political positions, thereby forming a government that brought about temporary calm.

However, independent groups within the government, unable to forge connections with internal counterparts, often developed significant ties with external powers. In other words, Consociational democracy inherently fostered the involvement of foreign forces in domestic political and governance structures. Over time, this led to the transformation of ethnic and religious groups into transnational paramilitary forces. Lebanon and post-Saddam Iraq are prime examples of this trajectory.

Exploring Lebanon’s Challenges from Three Political Perspectives

In this article, I aim to examine Lebanon’s situation through three political lenses and demonstrate how, given the presence of Consociational democracy on one hand and Islamism on the other, achieving the goals of Lebanon’s president is an exceedingly difficult task.

Countries like Lebanon have no choice but to embark on the arduous yet reliable path of nation-building and cultivating national consciousness. This process is essential for establishing a stable state and a unified identity. However, the greatest obstacle to this endeavor is Islamism, which inherently undermines the pursuit of national unity and cohesion.

First Perspective: “The Political”

What is politics?

This ontological question has existed for as long as human civilization. While politics can be defined in various ways, I refer to the modern concept of “The Political” as articulated by Carl Schmitt. According to Schmitt, the essence of “The Political” lies in the distinction between “Us” and “them.” Politics emerges whenever a group of people perceives a bond among themselves, calls themselves “Us,” and defines clear boundaries for others, identifying as “Them.”

The size and scope of the group that identifies as “Us” can vary, giving rise to political concepts and institutions on both small and large scales. When the inhabitants of a defined territory collectively refer to themselves as “Us,” the phenomenon of a “nation” comes into being. In essence, a nation is the manifestation of a shared sense of belonging among people living within specific territorial boundaries.

“The Political” also inherently involves recognizing those outside the group as “Them” or “Others.” For a nation, those outside its territorial borders are considered “Others.” Managing the conflicts between “Us” and “Them,” while also meeting the needs of “Us,” requires an institution or mechanism—the state. From this perspective, the state is a tool of politics, tasked with managing internal and external conflicts and ensuring the welfare of the nation.

The Interdependence of Nationhood and the State

As evident from the above discussion, the formation of a “nation” is intrinsically linked to the nature and functionality of the state as the tool of conflict management.

The guarantee of conflict management lies in the military force of a country. When the “Us/Them” dynamic within territorial boundaries aligns to form a unified internal “us” called the nation, the military’s role is confined to protecting the nation’s borders against external “others.” If any military force operates outside the scope of territorial protection, it undeniably signifies the absence of a unified “Us” as a nation.

Unfortunately, the politics in Lebanon reflects precisely this issue. The presence of a Consociational democracy is expected to exacerbate the divides among ethnic and religious groups. Allocating political positions based on religious affiliations inevitably strengthens sectarian identities at the expense of national unity.

The state can monopolize the legitimate use of power only when it is founded on a national bond, free from ethnic or religious biases. However, when religious and ethnic ties overshadow national ones, the state loses this monopoly. The existence of Hezbollah in Politics in Lebanon as an armed group is a stark manifestation of the lack of national awareness and a byproduct of the Consociational democracy system.

Hezbollah, an Islamist group representing Lebanon’s Shiite community, maintains stronger military and economic ties with the Shiite government of Iran than with Lebanon’s central government. This allegiance underscores the absence of a cohesive “Us” within Lebanon, leaving the nation fragmented and its political aspirations unfulfilled.

Second Perspective: Politics as Statecraft

Statecraft represents another dimension of politics, focusing on effective methods for managing internal conflicts within a state and maximizing benefits in foreign relations. The essence of politics is conflict, while statecraft aims to resolve conflicts and forge connections among people.

Statecraft arises from the understanding that no single normative or ultimate standard exists to resolve diverse and often incommensurable conflicts. Moral values, while helpful in many respects, cannot always be reduced to political values, making conflict inevitable. Statecraft, therefore, reflects the necessity of choosing between competing and sometimes irreconcilable values, especially in the absence of an authoritative principle or rule to settle disputes.

The Role of the Public Sphere in Statecraft

To facilitate statecraft, a clear distinction between the private and Public Spheres is essential, with the Public Sphere dedicated to political engagement. This separation allows for greater public participation and interaction without encroaching on private life. Within the Public Sphere, the interaction among individuals, groups, media, and social institutions enables the resolution of conflicts within the broader collective of the “nation.”

A critical element in achieving this lies in fostering horizontal and networked interactions among diverse units—be they individuals or groups. Decisions are not imposed from above or dictated by absolute rules; instead, they emerge from critical thinking, comprehensive deliberation, and the exchange of ideas. Such statecraft, grounded in these interactions within the Public Sphere, can address many of the inevitable societal divides.

Machiavelli viewed politics as the accumulation of knowledge developed to guarantee constructive conflict management, he also believed that freedom was the product of this knowledge. Freedom is assured as long as conflicts can exist without posing a threat to societal collapse.

Islamism: An Obstacle to Statecraft

The continuation of activities within the Public Sphere and the preservation of freedom require the exclusion of religions, especially political-religious ideologies like Islamism, from the political domain. The reasoning is simple: Islamism is inherently incompatible with horizontal and egalitarian relationships in the political arena. It fundamentally rejects critical thinking as a valid approach.

The common denominator among all Islamist movements—whether Salafi-Takfiri or religious intellectuals—is their call for a “return to the authentic teachings of Islam” from the early Islamic era. Such a belief legitimizes individuals who claim privileged access to “authentic” Islamic teachings through interpretation. These teachings are treated as immutable divine decrees, dictating how people should live. In such an environment, meaningful interaction and resolution of social divides become impossible.

The Path Forward for Politics in Lebanon

A unified nation with minimal social divides requires a conducive Public Sphere for interaction and engagement among individuals and groups. Once this is achieved, the establishment of a state with a monopoly on the legitimate use of force is no longer a distant goal.

From the perspective of statecraft, Lebanon’s political system demands significant reevaluation and profound transformation to overcome its current challenges.

Third Perspective: Political Rights

This dimension of politics addresses the mechanisms that construct a state. Concepts such as national awareness, the social contract, the delegation of power to the government, and similar ideas fall under the scope of political rights. Moreover, this aspect plays a decisive role in what is referred to as “absolute authority”—the entity or power that no law can limit, an extra-legal authority derived from a political right and directed toward a political action.

A constitutional state or political authority constrained by law can inspire a sense of security and optimism among its citizens. This liberal principle has been one of humanity’s aspirations in the modern era. However, while the importance of legal oversight and constraints cannot be overstated, they do not negate the need for an authority capable of acting decisively in extraordinary circumstances when laws are silent or insufficient.

The Role of Extralegal Authority

Many ideals associated with the rule of law—such as the alignment of law with justice—facilitate the formation of identity, foster trust, and reinforce compliance among citizens. Government institutions that remain insulated from the direct intervention of powerholders help eliminate certain disputes from political processes, thereby strengthening faith in the system. Belief in the law-governed nature of the state can serve as a powerful source of political legitimacy and contribute significantly to state-building.

However, the existence of Extralegal authority should not be ignored. Exceptional situations demand urgent and decisive action that transcends normal legal frameworks. Failure to recognize and prepare for such authority can lead to state collapse in times of crisis. At the same time, this authority carries inherent risks. Acting beyond the law can revive political theology, which grants supremacy to an authority beyond human constructs. This paradox can undermine the progress of humanity toward creating secular political systems where individuals coexist peacefully without religious affiliations dictating governance.

The resurgence of political theology under any guise threatens centuries of human effort to establish political order independent of religious influences. Unfortunately, this is precisely what Islamism has sought to achieve since the early 20th century.

The Way Forward For Politics In Lebanon

To address this challenge, societies may need to accept the risks of granting Extralegal powers to the executive branch or explore alternative approaches, such as plebiscites, citizen assemblies, or other forms of direct democracy. These mechanisms can offer a means of addressing crises without undermining the rule of law or resorting to political theology.

Conclusion

The existence of a single military force within a country is fundamental to state sovereignty and independence. General Joseph Aoun’s speech for this reflects a key characteristic of the modern state. However, as demonstrated in this article, achieving this goal hinges on conditions examined through three distinct political dimensions.

From each perspective, Lebanon’s political system—marked by Consociational democracy and the influence of Islamism—renders the independence of the Lebanese state and its monopoly on the legitimate use of force unattainable.

Politics in Lebanon must embark on the arduous but reliable path of nation-building. The greatest obstacle in this journey is Islamism, which continues to undermine the formation of a unified national identity.